Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Understanding Tests and Scientific Advances

Alzheimer’s disease represents one of the major global challenges in public health.…

Continue reading

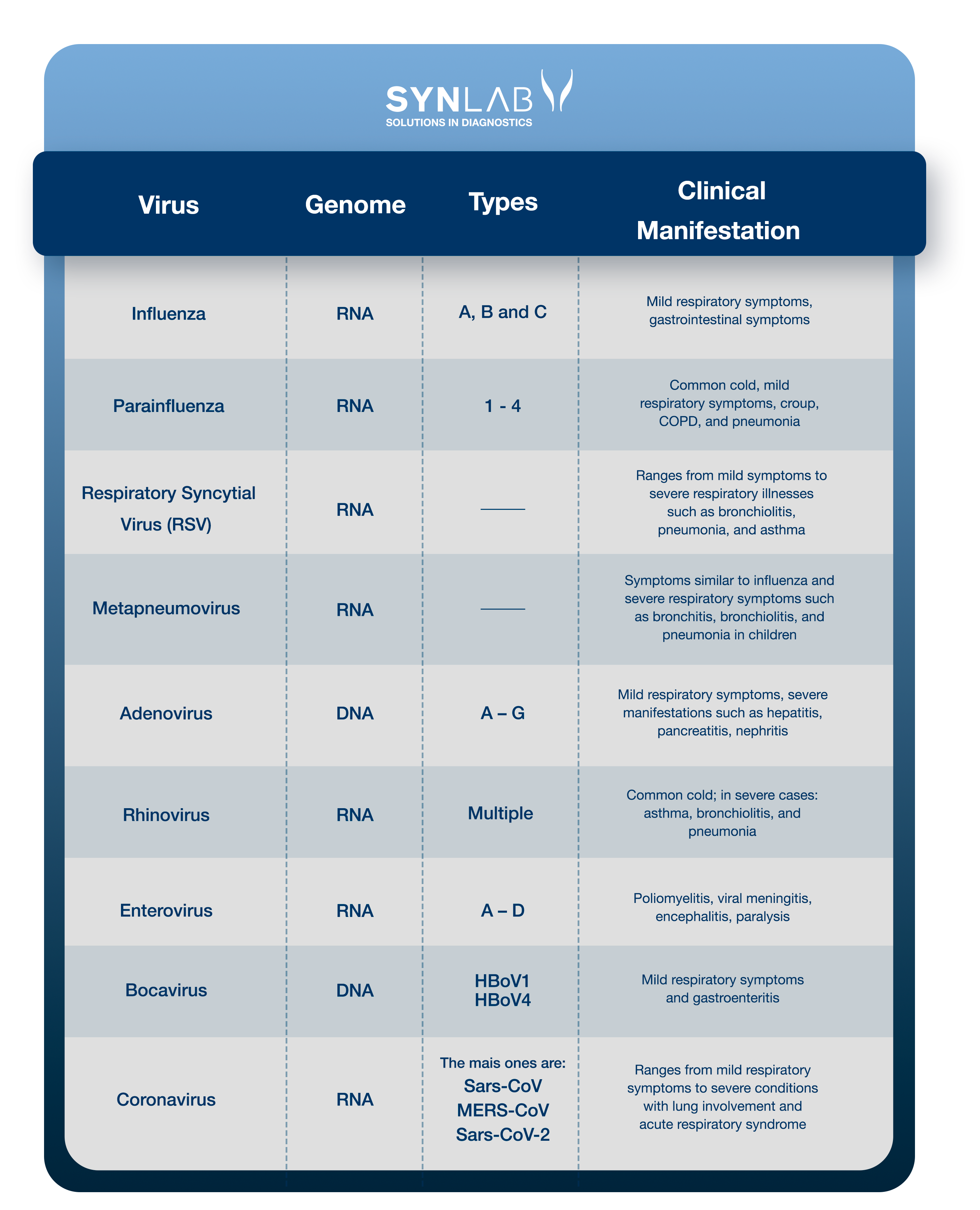

Emerging infectious diseases are frequently caused by respiratory viruses, which play significant roles in respiratory tract infections, ranging from the common cold to severe respiratory illnesses (1).

In the past 15 years, molecular detection and sequencing have enabled the increased identification of pathogens responsible for common respiratory diseases, as well as the identification of pathogens during pandemics (2).

Respiratory diseases encompass a range of conditions that affect the respiratory system, from the nose and throat to the lungs.

These diseases can be caused by various factors, including viral and bacterial infections, exposure to environmental pollutants, tobacco smoke, and other irritants. The severity of symptoms can range from mild to severe, and may include cough, difficulty breathing, chest pain, wheezing, and extreme fatigue.

According to the International Forum of Respiratory Societies, at least two billion people worldwide are exposed to toxic smoke from biomass fuels; and over two billion inhale pollutants and are exposed to tobacco smoke, resulting in a significant global health burden, with five respiratory diseases being among the most common causes of death worldwide (3):

Several new respiratory viruses have emerged, including Influenza A virus (also known as H1N1), avian influenza viruses A(H7N9) and A(H5N6), the coronavirus responsible for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) causing the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to over 14.9 million direct and indirect deaths worldwide between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021 (9-12).

Also check out the article “COVID-19 tests: Everything You Need to Know.”

Respiratory viruses are pathogens that infect the human respiratory tract, causing a range of illnesses from the common cold to more severe conditions like pneumonia and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

These viruses spread primarily through respiratory droplets expelled when coughing, sneezing, or talking, and can be transmitted both through direct contact with infected individuals and through contaminated surfaces.

The viruses most frequently involved in respiratory infections are rhinoviruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronaviruses, adenoviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and influenza viruses (13).

All of these viruses share the ability to transmit from person to person, and their transmissibility is influenced by the environment in which the pathogen and host are located.

Understand the viruses associated with respiratory tract infections and the related clinical conditions:

Read the details about each of them. If you prefer, click on the name to go to the section related to the virus:

Influenza is a respiratory infection caused by the influenza virus (Myxovirus influenzae) with significant morbidity and mortality rates worldwide. Influenza viruses are classified into types A, B, and C based on their nucleoproteins and matrix proteins (14).

Influenza, or the flu, typically causes mild respiratory problems such as:

Symptoms may persist for two to eight days.

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can occur in children. A minority of patients, especially the elderly, may experience severe illness due to viral or bacterial pneumonia (15).

Influenza type A and B viruses are responsible for seasonal epidemics, with the infection by influenza A virus (H1N1pdm09 and H3N2) characterized by the abrupt onset of:

The H1N1 subtype emerged from a quadruple combination of two swine viruses, an avian virus, and a human virus, causing the 2009 pandemic (16). Symptoms are usually mild, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, but can worsen, leading to pneumonia or respiratory failure.

The incidence and mortality of swine flu or H1N1 infection are higher among young adults and lower in elderly patients compared to seasonal flu, most likely because younger individuals have not been previously exposed to similar influenza viruses.

The virus was standardized as influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 to denote the pandemic and to distinguish it from seasonal H1N1 strains and the pandemic H1N1 strain.

Since 2011, outbreaks of the H3N2 subtype of swine origin have been predominantly reported in children. Additionally, the avian influenza or bird flu virus H5N1 has become a global concern (17).

As a preventive measure against influenza viruses, annual vaccination against the flu is recommended for everyone. Vaccination efforts should primarily target those at higher risk of complicated or severe influenza (the elderly and immunocompromised) and those who care for or live with high-risk individuals, including healthcare professionals. Current seasonal flu vaccines are also effective against the A (H1N1)pdm09 virus.

The parainfluenza virus (PIV) is an RNA virus from the Paramyxoviridae family, classified into four serotypes (PIV-1, PIV-2, PIV-3, and PIV-4), which causes various respiratory illnesses ranging from the common cold to flu-like syndrome or pneumonia. It is a known cause of infection in pediatric and immunocompromised patients, and is increasingly recognized as a relevant pathogen in hospitalized adults, with infection rates between 2% and 11% (18).

It is the second most common cause of lower respiratory tract infection in children.

Symptoms include:

There is evidence suggesting that PIV can result in recurrent and mildly asymptomatic infections in adult populations, with long periods of asymptomatic viral shedding (> 8 months) (19,20).

Serotypes 1 and 2 tend to cause epidemics in the fall, with each serotype occurring in alternating years. Serotype 3 is usually endemic and infects most children under one year of age, potentially causing pneumonia and bronchiolitis; while serotype 4 has cross-reactive antigenicity with the mumps virus.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is an enveloped RNA pneumovirus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family. It is the most important viral agent causing severe respiratory illnesses in infants and children worldwide (21).

RSV infections are responsible for one-third of deaths related to acute respiratory infections in infants under one year of age and are particularly problematic in premature infants, as well as in children with cardiac and respiratory issues. The virus also causes severe illness in the elderly.

Approximately 40 to 60% of children are infected with RSV in their first year of life, and more than 95% of children by the age of 2 will have had or will have at least one RSV infection (22).

Additionally, RSV infection is a major cause of morbidity in adults, particularly in the elderly and immunocompromised (23).

RSV is transmitted through contact with oral or nasal secretions of an infected person when they cough, sneeze, or talk, and indirectly through contact with contaminated surfaces and objects, causing recurrent infections throughout life. RSV infection triggers both innate and adaptive immune responses; however, immunity against the virus is not long-lasting. The transmission period begins two days before symptoms appear and only ends when the infection is controlled.

RSV has seasonal circulation, with higher detection rates in late fall and early spring. In tropical regions, it can be detected year-round.

The primary symptoms associated with RSV can range from mild symptoms (in healthy individuals) such as:

To more severe conditions such as acute bronchiolitis (inflammation of the bronchioles) and pneumonia (25).

Lower respiratory tract involvement occurs in approximately 15–50% of infants and children with primary infection, and hospitalization is necessary in 1–3% of cases in infants aged 2 to 6 months, who are at higher risk.

The acute phase of this infection is often followed by episodes of wheezing that recur over months or years and generally lead to a diagnosis of asthma.

Treatment includes bronchodilators and mucolytic agents, while high-risk young pediatric patients also receive prophylactic treatment with monoclonal antibodies (Palivizumab) (26).

Human metapneumovirus (HMPV) is a significant cause of upper and lower respiratory tract illnesses in children and adults. It is an RNA virus and a member of the Paramyxoviridae family, which also includes the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza viruses (27).

Metapneumovirus generally causes upper respiratory tract infections and flu-like illnesses, but it is also associated with lower respiratory tract infections such as: wheezing bronchitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia, particularly in very young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients (28, 29).

Symptoms generally include:

In infants under six months, the initial symptom may be a period of breathing cessation. Some small infants develop severe respiratory distress. In healthy adults and older children, the illness is usually mild and may only present as a common cold. Most children do not require hospitalization (30).

When necessary, nasal secretions are tested with a rapid antigen test, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique helps identify the virus.

Transmission occurs through direct contact with the infected person or through infected secretions. Home treatment primarily involves symptomatic relief.

Seroprevalence studies show that primary infection occurs before the age of 5, and individuals are reinfected throughout their lives; the four subgroups of HMPV vary from year to year (31).

Humoral immunity plays an important role in HMPV infection, and the study of HMPV antibodies provides valuable information, including HMPV seroprevalence, cross-serological protection between HMPV subgroups, and strategies for prophylaxis and therapy using monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (32).

Widely neutralizing monoclonal antibodies have significant clinical implications for the prophylaxis and treatment of high-risk patients.

Adenoviruses (AdVs) are DNA viruses that typically cause mild infections affecting the upper or lower respiratory tract and the gastrointestinal tract. Adenovirus infections are more common in young children due to the lack of humoral immunity (33).

There are seven species of human adenoviruses (A – G) and approximately 57 different serotypes. The predominant serotypes associated with diseases vary by country or region and may change over time (34).

Typical symptoms include:

Gastrointestinal symptoms may be present, particularly in children, and pneumonia occurs in up to 20% of newborns and infants (35).

Severe clinical manifestations are more likely in immunocompromised patients (transplant recipients, HIV infection) and occur in 10 to 30% of cases (36).

Adenovirus infections are increasingly recognized as causes of severe respiratory diseases and can result from exposure to infected individuals (inhalation of droplets, conjunctival inoculation) and contaminated objects.

The incubation period ranges from two to 14 days, and latent AdV can reside in lymphoid tissue, renal parenchyma, or other tissues for years; reactivation may occur in severely immunosuppressed patients (37).

Human rhinoviruses (RVs) are responsible for more than half of cold-like illnesses, being the most common cause of upper respiratory tract infections and costing billions of dollars annually in medical consultations and lost work and school days (38).

Approximately 50% of all colds are caused by one of the more than 100 existing rhinovirus serotypes, which are very common during the fall and spring and less common during the winter months.

The most common symptoms are (39):

Rhinoviruses are transmitted from person to person through direct contact with large airborne particles. HRV infection begins with intranasal and conjunctival inoculation, but not via the oral route. Scientific studies have shown that the virus is regularly deposited on hands and introduced into the environment, as it has been detected on 40% of the hands of naturally infected volunteers and on 6% of household objects (40).

Respiratory enteroviruses (EVs), like rhinoviruses (RVs), are small RNA viruses and are primary causes of upper respiratory tract infections, being among the most common infectious agents in humans worldwide (41).

Both belong to the Picornaviridae family and have been classified into seven distinct species, with three rhinovirus species (RV-A to RV-C) and four enterovirus species (EV-A to EV-D).

Despite being from the same family, these viruses have distinct characteristics; the tropism (the ability of a virus to specifically infect certain cells of an organism) of RVs is restricted to the upper respiratory tract, except in some rare cases, while EVs can infect a wide range of different cells and cause very diverse clinical conditions (42,43).

Diseases caused by EVs range from:

While other types of enteroviruses are primarily found in the respiratory tract and cause symptoms similar to those of rhinoviruses, enteroviruses of species C and D, known as respiratory enteroviruses, can also cause a range of symptoms.

The virus is mainly transmitted through direct contact or via contaminated objects (fomites), usually with inoculation into the eye or nose via the tip of the finger. These viruses are capable of surviving on hands for several hours, allowing for easy person-to-person transmission in the absence of proper hand hygiene, especially in the presence of high viral loads (44).

Human bocavirus (HBoV) is a parvovirus, isolated about a decade ago, found in respiratory samples, primarily in children aged 6 to 24 months with acute respiratory infections, and in stool samples from patients with gastroenteritis (45). Since then, three additional subtypes of HBoV (HBoV1) have been identified in stool samples and named HBoV2, HBoV3, and HBoV4. The virus has also been detected in other biological samples such as blood, saliva, and urine, as well as in river water and wastewater (46).

HBoV primarily affects children aged 6 to 24 months with respiratory symptoms such as:

HBoV2, like the other subtypes, is more frequently found in stool samples and is associated with gastroenteritis, as possibly HBoV3. Recent studies show that HBoV can be specifically detected in tissues such as the duodenum, nasal mucosa, and intestinal biopsies (47,48).

Bocavirus enters the body through the respiratory tract, bloodstream, or direct ingestion, reaching the gastrointestinal tract. Cases of HBoV infection show a high rate of co-infections with other respiratory and gastroenteritis pathogens such as human rhinovirus, adenovirus, norovirus, and rotavirus (49).

Coronaviruses are a family of enveloped RNA viruses classified under the order Nidovirales. This family includes pathogens that affect various animal and human species, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) (50).

Human coronaviruses were previously known only to cause the common cold until 2003, when SARS-CoV was responsible for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

Coronaviruses cause both acute and chronic respiratory diseases, as well as enteric and central nervous system (CNS) diseases in animals and humans (51). The most common types that infect humans are:

SARS infection presents a broad clinical picture, primarily characterized by fever, dyspnea, lymphopenia, and lower respiratory tract infection (55). Gastrointestinal symptoms and diarrhea are also common. Infected individuals may show slightly decreased platelet counts, prolonged coagulation profiles, and mildly elevated serum liver enzymes. Airborne droplets from infected patients are suggested to be the primary mode of transmission.

The discovery of the ACE2 enzyme in human cells as the receptor for SARS-CoV (187) demonstrated how SARS-CoV enters host cells and has allowed the elucidation, at the molecular level, of SARS-CoV cross-transmission (56).

For more information on SARS-CoV-2, refer to our article.

Preventing respiratory viruses is closely linked to basic hygiene practices, such as:

Avoiding crowded places and maintaining distance from individuals showing signs of illness are important measures to control the spread of viruses.

Diagnosis of respiratory infections is typically clinical, based on the manifestation of symptoms such as the common cold, bronchiolitis, croup, or pneumonia, and local epidemiology.

However, advancements in molecular methods have facilitated the detection and characterization of various virus groups and strains. These methods are essential, particularly when identifying the specific pathogen alters clinical treatment and for determining the cause of an outbreak.

Synlab provides a molecular panel for respiratory viruses, covering both DNA and RNA pathogens responsible for respiratory diseases. This panel includes the detection of the following viruses:

Samples can be collected from the upper respiratory tract (nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs) and the lower respiratory tract (BAL, sputum, and/or BAS) using swabs or scraping from the affected site.

Detection is performed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Accurate and up-to-date testing is essential for precise diagnosis and effective treatment guidance. At SYNLAB, we are here to assist you.

We provide diagnostic solutions with rigorous quality control to companies, patients, and healthcare providers. With over 10 years in Brazil, we operate in 36 countries across three continents, and we are leaders in service provision in Europe.

Contact the SYNLAB team to learn more about the available tests.

1. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427.

2. Schuster JE, Williams JV. Emerging Respiratory Viruses in Children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(1):65-74.

3. GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Jan 7;389(10064):e1

4. Burney PG, Patel J, Newson R, Minelli C, Naghavi M. Global and regional trends in COPD mortality, 1990-2010. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1239-1247.

5. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108.

6. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

7. The Global Asthma Report 2018. Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network, 2018

8. World Health Organization. Influenza (Seasonal). October 2023.

9. Cheng VC, To KK, Tse H, Hung IF, Yuen KY. Two years after pandemic influenza A/2009/H1N1: what have we learned?. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(2):223-263.

10. To KK, Chan JF, Chen H, Li L, Yuen KY. The emergence of influenza A H7N9 in human beings 16 years after influenza A H5N1: a tale of two cities. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(9):809-821.

11. Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):465-522.

12. World Health Organization. 14.9 million excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 [Internet]. 5 May 2022.

13. DOLIN R. Common viral respiratory infections and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In: FAUCI, A.S. et al.. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17 ed.. Philadelphia: MacGraw-Hill, 2007.

14. Gaitonde DY, Moore FC, Morgan MK. Influenza: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(12):751-758.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Influenza. 2022

16. Dawood FS, Iuliano AD, Reed C, et al. Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study [published correction appears in Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Sep;12(9):655]. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(9):687-695.

17. Duwell MM, Blythe D, Radebaugh MW, et al. Influenza A(H3N2) Variant Virus Outbreak at Three Fairs – Maryland, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(42):1169-1173. Published 2018 Oct 26.

18. Henrickson KJ. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(2):242-264. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.2.242-264.2003

19. Hutchinson AF, Ghimire AK, Thompson MA, et al. A community-based, time-matched, case-control study of respiratory viruses and exacerbations of COPD. Respir Med. 2007;101(12):2472-2481.

20. Peck AJ, Englund JA, Kuypers J, et al. Respiratory virus infection among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: evidence for asymptomatic parainfluenza virus infection. Blood. 2007;110(5):1681-1688.

21. Lozano R, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012; Volume 380: 2095-2128.

22. Instituto Fernandes Figueira – Fiocruz. Prevenção de infecção pelo vírus sincicial respiratório (VSR) em unidades neonatais e na comunidade. 2019

23. Rezaee F, Linfield DT, Harford TJ, Piedimonte G. Ongoing developments in RSV prophylaxis: a clinician’s analysis. Curr Opin Virol. 2017;24:70-78.

24. Bloom-Feshbach K, Alonso WJ, Charu V, Tamerius J, Simonsen L, et al. (2013) Latitudinal Variations in Seasonal Activity of Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV): A Global Comparative Review. PLOS ONE 8(2): e54445.

25. Houben ML, Bont L, Wilbrink B, et al. Clinical prediction rule for RSV bronchiolitis in healthy newborns: prognostic birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):35-41.

26. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines Committee. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e620-e638.

27. van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7(6):719-724.

28. Stockton J, Stephenson I, Fleming D, Zambon M. Human metapneumovirus as a cause of community-acquired respiratory illness. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(9):897-901.

29. Pelletier G, Déry P, Abed Y, Boivin G. Respiratory tract reinfections by the new human Metapneumovirus in an immunocompromised child. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(9):976-978.

30. Ebihara T, Endo R, Kikuta H, Ishiguro N, Ishiko H, Hara M, Takahashi Y, Kobayashi K. Human metapneumovirus infection in Japanese children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Jan;42(1):126-32.

31. Ebihara T, Endo R, Kikuta H, et al. Human metapneumovirus infection in Japanese children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(1):126-132.

32. Schuster JE, Williams JV. Human Metapneumovirus. Microbiol Spectr. 2014;2(5):10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0020-2014.

33. Lynch JP 3rd, Kajon AE. Adenovirus: Epidemiology, Global Spread of Novel Serotypes, and Advances in Treatment and Prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37(4):586-602.

34. Erdman DD, Xu W, Gerber SI, et al. Molecular epidemiology of adenovirus type 7 in the United States, 1966-2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(3):269-277.

35. Chang SY, Lee CN, Lin PH, et al. A community-derived outbreak of adenovirus type 3 in children in Taiwan between 2004 and 2005. J Med Virol. 2008;80(1):102-112.

36. Kim YJ, Boeckh M, Englund JA. Community respiratory virus infections in immunocompromised patients: hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplant recipients, and individuals with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(2):222-242.

37. Ison MG. Adenovirus infections in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(3):331-339.

38. Bertino JS. Cost burden of viral respiratory infections: issues for formulary decision makers. Am J Med. 2002;112 Suppl 6A:42S-49S.

39. Pappas DE, Hendley JO, Hayden FG, Winther B. Symptom profile of common colds in school-aged children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(1):8-11.

40. Gwaltney JM Jr, Moskalski PB, Hendley JO. Hand-to-hand transmission of rhinovirus colds. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(4):463-467.

41. Royston L, Tapparel C. Rhinoviruses and Respiratory Enteroviruses: Not as Simple as ABC. Viruses. 2016 Jan 11;8(1):16.

42. Tapparel C, Siegrist F, Petty TJ, Kaiser L. Picornavirus and enterovirus diversity with associated human diseases. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;14:282-293.

43. Romero JR, Newland JG. Viral meningitis and encephalitis: traditional and emerging viral agents. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2003;14(2):72-82.

44. L’Huillier AG, Tapparel C, Turin L, Boquete-Suter P, Thomas Y, Kaiser L. Survival of rhinoviruses on human fingers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(4):381-385.

45. Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples [published correction appears in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Oct 25;102(43):15712]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(36):12891-12896.

46. Kapoor A, Slikas E, Simmonds P, et al. A newly identified bocavirus species in human stool. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(2):196-200.

47. Jartti T, Hedman K, Jartti L, Ruuskanen O, Allander T, Söderlund-Venermo M. Human bocavirus-the first 5 years. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22(1):46-64.

48. Santos N, Peret TC, Humphrey CD, et al. Human bocavirus species 2 and 3 in Brazil. J Clin Virol. 2010;48(2):127-130.

49. Schildgen O. Human bocavirus: lessons learned to date. Pathogens. 2013;2(1):1-12. Published 2013 Jan 11.

50. Weiss SR, Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005 Dec;69(4):635-64.

51. McIntosh, K. (1974). Coronaviruses: A Comparative Review. In: Arber, W., et al. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology / Ergebnisse der Mikrobiologie und Immunitätsforschung. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology / Ergebnisse der Mikrobiologie und Immunitätsforschung, vol 63. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

52. Ebihara T, Endo R, Ma X, Ishiguro N, Kikuta H. Detection of human coronavirus NL63 in young children with bronchiolitis. J Med Virol. 2005;75(3):463-465.

53. Woo PC, Lau SK, Chu CM, et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol. 2005;79(2):884-895.

54. Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1953-1966.

55. Tsui PT, Kwok ML, Yuen H, Lai ST. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: clinical outcome and prognostic correlates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(9):1064-1069.

56. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450-454.

57. Chan JFW, et al. The emerging novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: The “knowns” and “unknowns”. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2013; Volume 112: 372-381.

58. Al-Tawfiq JA, Hinedi K, Ghandour J, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a case-control study of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):160-165.

Alzheimer’s disease represents one of the major global challenges in public health.…

Continue reading

Nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics have become central fields within precision medicine,…

Continue reading

Men’s health goes far beyond urological exams. It involves comprehensive…

Continue reading